The mushroom sector is entering a transformative phase, where farming tradition meets cutting-edge innovation. Once seen simply as a niche crop, mushrooms are now emerging as powerful contributors to sustainable agriculture, human wellness, and even material science.

Shaping a circular food system

One of mushrooms’ greatest strengths lies in their resource efficiency. Unlike many crops, they flourish on byproducts such as straw, sawdust, or coffee grounds, making them natural allies in the shift toward circular farming. For growers, this opens opportunities to reduce waste, diversify substrates, and partner with other agricultural industries to create closed-loop systems.

Health on the rise

Consumer interest in functional and nutrient-rich foods continues to surge, and mushrooms are at the forefront. Varieties like Lion’s Mane and Reishi are valued for their adaptogenic potential, while everyday favorites such as oyster and button mushrooms are being recognized for their protein, fiber, and vitamin D. This dual reputation, both as staple food and functional ingredient, is fueling new product development across the food and supplement industries.

Farming smarter with technology

The drive toward efficiency and scalability has accelerated adoption of digital tools. Automated climate systems, AI-based monitoring, and sensor-driven data analytics are helping growers fine-tune production while tackling labor shortages. Farms that embrace these technologies are finding new ways to improve yields, cut costs, and meet rising demand with consistency.

Beyond the plate

Mushrooms are increasingly breaking into non-food markets. Mycelium, the root-like structure of fungi, is now being used to create biodegradable packaging, sustainable textiles, and even construction materials. These developments highlight the mushroom industry’s potential to play a role far beyond food, positioning it as a cornerstone of sustainable innovation.

Building a future-ready industry

As mushrooms gain attention worldwide, the industry faces both opportunity and responsibility. Growth must balance innovation with sustainability, ensuring practices that protect natural resources while meeting expanding consumer expectations. Collaboration between farmers, researchers, and entrepreneurs will be vital in keeping the sector resilient.

Mushrooms today are not only a crop but a vision of what agriculture and innovation can achieve together. For farmers and industry leaders, the message is clear: cultivating mushrooms means cultivating the future.

In the following weeks we'll dive deeper into theses subjects. Do you have expertise, research or success stories on these subjects that can inspire others? Reach out and let’s share your voice with our readers!

A study from Singapore shows that people who eat more than two portions of mushrooms per week have a 47% lower risk of developing Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).

What is MCI?

MCI is a condition in which memory, concentration, or other cognitive functions are slightly below what is normal for one’s age, while daily functioning remains largely intact. It is considered an early warning sign of dementia, though not every case of MCI progresses to it.

How mushrooms help

Scientists believe that certain compounds in mushrooms, such as antioxidants and bioactive substances may help protect brain cells from oxidative stress.

Important to know

The study is observational: it shows associations, but not necessarily cause-and-effect.

Further research and clinical studies are needed to understand exactly which mushroom varieties and dosages are most effective.

Inspired by research published via PMC (National Library of Medicine)

When you think of mushrooms, you might picture them on your plate. But researchers in Spain are showing how fungi can also shape the future of packaging. Their latest project turns mushroom mycelium into a biodegradable, durable material that can replace plastic.

This is part of a growing global movement: companies in the US, Europe, and Asia are all exploring how fungi can tackle one of the world’s biggest waste challenges. By transforming side streams and agricultural by-products into packaging, mycelium offers a double win, reducing plastic pollution and making better use of resources.

For mushroom growers and industry players, it’s another example of how fungi are stepping outside the farm and into mainstream innovation.

Ecovative, a pioneer in mycelium-based technologies for sustainable food and materials, today announced the sale of its Netherlands-based subsidiary, Ecovative Spawn & Substrate BV, to the Klerken family, founders of Scelta Mushrooms.

Under the Klerken family’s ownership, the business will be renamed OurCelia, marking a new chapter in its support of the mushroom industry and introducing new solutions to mushroom farmers globally. This transition reflects a marriage of strengths: Ecovative’s leadership in mycelium innovation, stretching two decades, and the Klerken family’s deep roots in the global mushroom industry, dating back to 1963. Together, the two organizations will maintain a close, long-term relationship to advance the supply of world-class spawn products to both mushroom and mycelium producers. Ecovative previously acquired Lambert Spawn Netherlands in 2022 from its U.S. parent company, Lambert Spawn, founded in 1919 and recognized as the world’s oldest spawn producer. With this foundation, the Dutch spawn activities are now continuing under the Klerken family as OurCelia.

“Ecovative is proud to have grown the global supply chain for Agaricus and AirMycelium spawn from the Netherlands, and we are confident that under the Klerken family’s stewardship, OurCelia will thrive as a dedicated supplier to mushroom growers and mycelium producers worldwide,” said Eben Bayer Co-founder and CEO, Ecovative. “This step allows Ecovative to sharpen its focus on scaling AirMycelium production across our food and materials businesses in the United States, while ensuring the Dutch spawn business continues to serve the industry with excellence.” “The mushroom industry has been at the heart of our family for generations,” said Jan Klerken Sr., founder of Scelta Mushrooms. “With OurCelia, we are building on that heritage by expanding our business to include spawn and substrate production. This is a natural continuation of our commitment to advancing mushroom cultivation and supporting growers for decades to come.” In addition, Ies Hooglugt will continue in his role as managing director, ensuring continuity and trusted leadership for employees, customers, and partners of the company

Looking Ahead with OurCelia

For the Klerken family, OurCelia is more than a new company — it is a bold step to shape the future of the mushroom industry. With deep roots that stretch back generations, the family has always believed in the power of mushrooms to nourish people and transform industries. OurCelia will build on that legacy by reimagining spawn and substrate production for a new era, delivering cutting-edge solutions that help mushroom farmers grow stronger businesses, diversify their crops, and expand into new markets. By combining tradition with forward-looking innovation, the Klerken family aims to make OurCelia a global leader in advancing fungi as a cornerstone of sustainable food, agriculture, and materials for decades to come.

About OurCelia

OurCelia is a Dutch producer of high-quality mushroom spawn and substrates, rooted in decades of expertise within the global mushroom industry. Founded in 2025 following the acquisition of Ecovative Spawn & Substrate BV by the Klerken family, also founders of Scelta Mushrooms, the company builds on a long heritage of innovation and entrepreneurship in mushroom cultivation. By combining tradition with cutting-edge technologies, OurCelia supports growers worldwide with reliable, sustainable solutions that strengthen their businesses and open new opportunities for the future.

A smile on our customer’s face is the best reward

Watch the delivery of harvesting trolleys to the Sopińscy mushroom farm

GrowTime has just delivered modern mushroom harvesting lorries to the Sopińscy farm. This is another step toward more efficient and comfortable harvesting.

We’ve prepared a short video where you can see how the delivery went and how our solutions look in practice.

We are proud to support the growth of Polish mushroom producers. Watch the delivery video below!

The Future is Fungi Award is back, championing pioneering solutions that harness fungi and mycelium to tackle some of today’s biggest environmental challenges. The initiative aims to help startups and science entrepreneurs turn their ideas into impactful businesses.

For startups

- € 250,000 SAFE investment to accelerate growth

- Access to a global expert network across corporates, research institutes and startup mentors (including L’Oréal, Novonesis, Stanford, BASF and DSM-Firmenich)

- Visibility through the Fungal Hall of Fame and international media features

For science entrepreneurs

- A three-month venture builder program to transform research into a startup

- Financial support to kick-start the journey

- Access to the same worldwide network of experts

- Recognition and media coverage for the global winner

Key dates

- Startups: applications open September 10 - October 1

- Science entrepreneurs: applications open in December

With the Future is Fungi Award, innovators get a chance to bring their ideas to a global stage, and help build a more sustainable future.

Find out more and apply at www.futureisfungi.org.

BDC Annual Conference 2025 set for Leipzig

From 25–27 September 2025, the German Association of Mushroom and Cultivated Mushroom Growers (BDC) will host its traditional annual conference at the H4 Hotel in Leipzig. The three-day event combines professional discussions, technical updates, and cultural highlights for mushroom growers and industry partners.

Highlights include:

- Closed committee meetings and the members’ general assembly (including a new chair election).

- Public lectures on the Healthy Mushrooms promotion campaign, mushroom production in Switzerland, and current challenges for European growers.

- Sessions on AI in harvesting and predicting the right picking time, plus a planned talk on cybersecurity for farms.

- A presentation by Prof. Dr. Fritz-Gerald Schröder exploring how taste develops in mushrooms.

Participants can also join a tour of Pilzhof Pilzsubstrat Wallhausen GmbH on Saturday morning, and enjoy networking dinners — including an evening at Leipzig’s historic Auerbachs Keller.

More details and registration: BDC Annual Conference

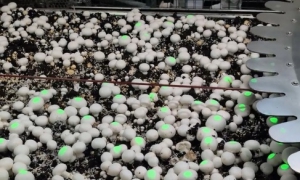

Canadian agtech company Mycionics has introduced its newest innovation, the Crop Scout, now live at South Mill Champs Mushrooms.

The system scans each mushroom in real time and uses a green light to show harvesters exactly which ones are ready to pick.

By guiding workers to optimal mushrooms, Crop Scout helps farms achieve 4–8% higher yields and improves harvesting efficiency by around 15%. For an industry where labour and timing are critical, this selective approach can significantly cut waste and standardise quality.

The rollout was developed in partnership with South Mill Champs and Christiaens Group BV, marking another step forward in applying robotics and AI to commercial mushroom production.

Article of Mycostories in partnership with Solid Fermentation Innovation a consulting company specializing in research, development, scale-up and downstream processes of solid-state fermentation based products.

Solid-State Fermentation (SSF) has been with us for centuries. From koji and tempeh in Asia to traditional fermented cheeses and starters in Europe, SSF was how many cultures learned to work with microbes long before we used bioreactors and autoclaves. In the 1960s and 70s, the technique found a new home in enzyme production, with fungi used to produce amylase, chitinase, and proteases at commercial scale. Around the same time, SSF also entered the agricultural world as a method for producing biocontrol agents, mostly fungal spores grown on solid carriers.

Why Solid-State Fermentation Is Gaining Ground

But in the last three to five years, something big has shifted. We’ve seen a surge of interest in SSF across multiple industries. Why now? The reasons are both practical and cultural. On the one hand, SSF offers a compelling business case: it typically requires lower CAPEX (capital expenses) and OPEX (operational expenses) than submerged fermentation, it supports circular economy models through the use of agro-waste and side streams, and it enables the production of a wide diversity of metabolites and biomass types. On the other hand, the cultural rise of fungi, from gourmet mushrooms to mycelium leather, has helped shine a light on SSF as a forgotten but powerful platform.

A growing, cross-sector wave of innovators is embracing SSF. As Dr. Barak Dror, co-founder and CEO of Solid Fermentation Innovation (SFI), puts it: “We saw early signs of this shift and started tracking it closely, what emerged was a broad movement across industries, each adapting SSF to their own needs.” SFI’s recently updated open-access database lists over 90 companies, from meat alternative startups to biocontrol firms, now applying SSF to produce everything from mycoprotein and enzymes to packaging foams and active pharmaceutical ingredients. That breadth tells a story: while SSF is still considered niche, it’s quickly gaining traction as a promising method for working with fungi and other microorganisms in high-impact applications.

Please read the full article here.

Source: Mycostories

Compost-casing-mushroom water relationships

The function of casing is to induce fruiting, support mushroom growth, and provide a source of water to the mushroom that compensates for its water lost through evaporation and transpiration. Sometimes, there has been an overemphasis on the influence of the moisture layer in the casing on mushroom yield and quality. A large variation in the compost substrate moisture may have more influence on mushroom yield and fresh mushroom quality. It is not to say that casing moisture does not influence yield or quality, but it may take a larger disparity in moisture to markedly influence the end product.

The mushroom relies on water potential gradients to move water through the mycelium. Water flows from regions of higher water potential to lower water potential, which helps maintain turgor pressure necessary for mycelial tip extension and growth. This same gradient also affects nutrient transport: nutrients, ions, and metabolites often move along with water via bulk flow or are actively transported across membranes, but their distribution is shaped by the underlying water potential differences within the mycelial network and between the fungus and the compost.

In a mycelial network, water potential gradients help the translocation of nutrients—moving them from the compost, the resource-rich region, to actively growing hyphal tips or fruiting bodies. Under dry conditions, the external water potential becomes too low, water movement into the hyphae slows, reducing nutrient uptake and impairing growth. Conversely, favorable water potential promotes efficient uptake and redistribution of resources throughout the mycelium.

Think of thicker rhizomorphs in the casing as the big pipes that move water and nutrients from the compost to the developing mushrooms. To keep mushrooms healthy and productive, this pipe system needs to stay in good working order all through the crop. Just like it’s easier to move water through a fire hose than a garden hose, well-developed rhizomorphs make water delivery more efficient. Keeping the casing wet or moist is what allows these larger “pipes” to form and continue feeding the mushrooms. If the casing dries out during production, most strains will give lower yields and poorer quality mushrooms. In the end, this whole water network relies on the compost as the main source of water for the crop.

Water is constantly moving during the cropping cycle. Mushrooms take up water into their cells, while water is also lost through evaporation and transpiration. Growers replace this loss mainly by watering the casing layer. However, we still know little about exactly how mushroom mycelium absorbs and transports water, or how water moves through rhizomorphs into the mushroom itself.

Some research suggests that water uptake depends on differences in water potential between the mycelium and the compost solution (Kalberer, 1987). As cropping progresses, mushrooms use water from both the compost and casing, while evaporation, transpiration, and respiration continually reduce the water content of the crop. This loss lowers the water potential inside mushroom cells. Because water moves from higher to lower potential, this gradient may allow mushrooms to absorb water with little energy cost. Another idea is that nutrient absorption helps drive water uptake (Holtz, 1971; 1979; Schroeder & Schisler, 1981; Kalberer, 1987). When nutrients are actively absorbed by the mycelium, the osmotic potential inside the cells decreases. Water then follows passively, moving in response to the concentration of nutrients. The developing mushrooms produce the sugar mannitol and therefore have a much higher concentration than the vegetative mycelium (Holtz, 1976). It was suggested that this different concentration of mannitol creates the osmotic and water potential gradient responsible for “pumping” nutrients and water from the compost mycelium through the casing rhizomorphs and into the developing mushrooms.

In summary, mushroom fruit body development depends on a balance of water movement between the compost, casing, and the developing fruit mushrooms. While casing moisture is important for yield and quality, compost moisture may play an even greater role. Water and nutrients move through the mycelium by water potential gradients, flowing from wetter regions in the compost toward drier hyphal tips and mushrooms. Rhizomorphs act like large pipes, efficiently transporting water and nutrients when casing moisture is maintained; if the casing dries, yields and quality decline. Water uptake is largely passive, driven by gradients in water and osmotic potential, which are influenced by nutrient absorption and the accumulation of compounds like mannitol in mushrooms. Together, these processes form a dynamic water transport system that sustains mushroom development throughout cropping.

REFERENCES

Holtz, R.B. 1971. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of free neutral carbohydrates in mushroom tissue by gas-liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. J. Agr. Food Chem. 19 (6):1272-1273.

Holtz, R.B. and Smith, D.E. 1979. Lipid metabolism of mushroom mycelia. Mushroom Sci. 10 (Part 1):437-444.

Kalberer, P.P., 1987. Water potentials of casing and substrate and osmotic potentials of fruit bodies of Agaricus bisporus. Sci. Hort. 32:175-182.

Schroeder, G.M. and Schisler, L.C. 1981. Influence of compost and casing moisture on size, yield, and dry weight of mushrooms. Mushroom Sci. 11:495-509.